We must decide “What we change and what we preserve…”

Anthropologist and an Anishinaabek (Ojibwe) Sonya Atalay in Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities presents that archaeology is at an exciting juncture right now as the discipline explores new facets and ways of knowing towards archeological research. The past two decades have brought forward important changes to the how archaeologists see the communities they study, and how they engage in relations with them. Notably, the creation of this project was to open up a different way of knowing through use of traditional knowledge, life ways, and the Indigenous mind-set of the world around them. Thinking critically of where the discipline will go archaeologists have moved toward community engagement and community-based archaeology. However, Atalay explains that as we look at the way archaeology is being shaped, three important considerations present themselves: the issue of relevance, the question of audience, and concerns about the benefits. In the past, archaeologists were troubled by how their archaeological research related to society, and it was often said that the modern world was capable of moving forward without archaeology.

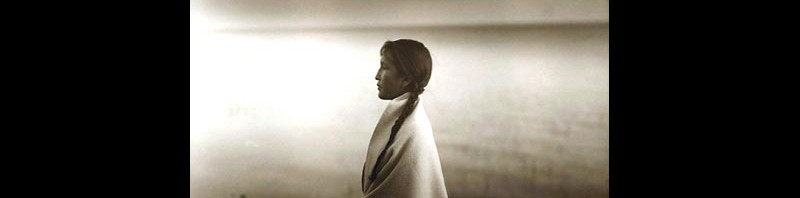

However, as archaeology progresses we see a rise in movement towards community engagement following the activism of the 1970s and 1980s with the Red Power Movement. It is not to say however, that the Red Power Movement was the reason why archaeology began to change its ways, but the activism of Native American peoples in the United States and Canada brought forward the movement that archaeology has been waiting for. Post-processualism brought forward “discussions of self-reflexivity, multi-vocality, and the role of the subject emerged.” Pushing the discipline into its current position, collaboration now included community-based participatory research. The period during the Red Power Movement saw the rise of many groups such as The American Indian Movement, who argued against the exhibition of ancestral remains in museums. The Indigenous voice was heard all throughout North America and changes to legislation, the need for alternative methodologies in archaeology, and this led to the engagement that we see, or want to see, today.

Engaging with Native communities allowed new relationships to grow and collaborations flourished. We see in the 2000s a large part of material be published that is from the point of view of Indigenous peoples. Primarily, by establishing a community-based relationship for projects we witness how research did not only benefit one side but was with and for communities. Reciprocity became a key feature and both academic and community partners benefited.

And where are we now?

Atalay’s research presents a detailed history of community engagement from the United States but we are able to use it for Canadian benefit. She goes on to express that Native peoples are at the end of the day, are people, and their involvement in a project is not only during research and fieldwork, but requires involvement past a professional level.

First Nation communities can be hesitant towards archaeologists and the practice, but the ability to write and be a part of their own historical narrative moves past the colonial harness and into an age of betterment, honesty, kindness, and truth. Since it is in the teachings of many First Nation communities to remember their teachings and to ensure they are on the path the Creator has made. At the end of the day, it is better to get a no, then wonder what could have been.